(Read Part one here).

We’ve already seen that design is a problem solving exercise. And without a good problem to solve, what are you doing making a digital product? Of course, some apps exist as a means of expression, experimentation or pure fun (and even these, you’d argue, are solving problems in their own way), but if you’re at all serious about launching an app which is intended for wider distribution and commercial success, be prepared to ask yourself some searching questions about your intentions.

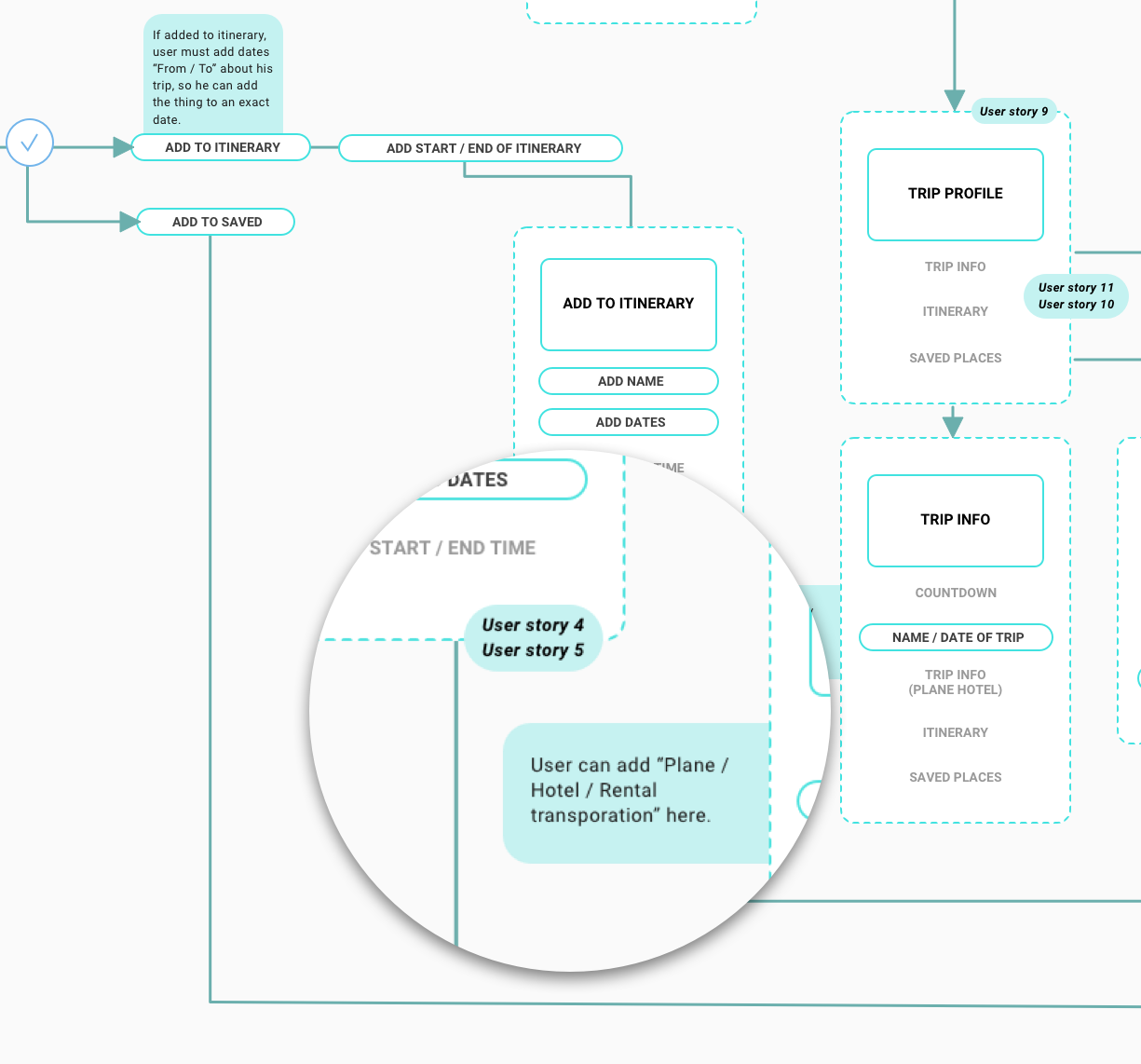

Product designer Boris’ sitemap for a client based on user research & feedback.

Product designer Boris’ sitemap for a client based on user research & feedback.

Even better, get somebody to ask you them, with the unflagging persistence of a five-year-old being sent to bed early on a weekend. Or get a five-year-old to ask you about your app idea themselves.

It’s a surefire way to quickly expose holes in your reasoning. What’s the one answer that’s most insulting, most unsatisfactory and most frustrating to the five-year-old’s ‘why’?

‘Because I said so.’

It’s also the most dangerous to the wannabe app founder. It stinks of assumption. You should never embark on a journey of building a digital product armed only with a handful of unconfirmed assumptions: if your product is to succeed it must meet a real need, solve a real problem.

What’s a real problem in this context? Well, we might amend the adage ‘a problem shared is a problem halved’ to ‘a problem shared by a significant portion of your target demographic is a problem worth considering.’

There has to be a ‘me too’ factor for your app to have reach, and that means you’ve identified a real base of people who would self-identify as having this problem you want to solve. We’ll talk more about user research later in this series: suffice to say, if you haven’t been out talking to your target audience, start now. And listen to what they say, not whether they’re agreeing with your opinions, but what they actually say in their own words when talking about their needs.

Most of us install and discard apps all the time; they fizzle like moths around a bonfire. We very quickly see whether an app is meaningful, useful and engaging.

Not only does there have to be evidence that this problem is real and solvable, it has to matter enough for your audience to want to do something about it. Marketers talk about ‘pain points’ and it sounds somewhat predatory or cynical, but it’s a useful shorthand for understanding how the human psyche works.

We’re selfish, we humans. We don’t care about your financial goals or marketing department’s drive for innovation or your misplaced sentiment of drumming up new business. We care about whether your product gives us something we need, in a way that’s better than our current reality or workaround.

For example, here at Despark we worked with the charity Best Beginnings to put their video and online resources into the hands of expectant and new parents, so they could access support even when they couldn’t move from the sofa. Our team is currently helping innovators Altrix roll out the first phase of their hybrid agency model, which puts control and money back in the hands of the UK’s hospitals and band 5 locum nurses (the problem being the £400 million spent annually by the NHS on agency fees, and the risk of many last minute shifts going understaffed.)

Both these projects had comprehensive discovery stages, and both started with identifying a set of problems, needs and assumptions and working our way through them to find clarity.

So what about you? Are you on your way to being able to answer these questions?

- Who (specifically) are you solving the problem for?

- How would it make these people’s lives easier?

- What greater impact would it have?

If you’ve identified that you don’t know the answers yet, don’t panic. It’s normal to find gaps in your knowledge or research. Write down what you do have, and next time we’ll go through some specific scenarios to help you identify what kind of research you need to do more of, whether you’re a young startup or an established business wanting to make the move into digital.

If you can sit down and paint a detailed picture of a real person whose problem your app would solve, give them a name, an age, a job, a pet and an income, a list of fears and worries, and describe a scenario in which your app would improve their life in tangible ways, then you’re on the right track. You’ll have to limber up your empathy muscles here. When you design human-first products, as we do, you have to be able to see the world as others do.

Red flags

If the thought of doing this type of research or thinking is unappealing, it’s likely your idea won’t have the legs to get to market: product development is intense and you’ll need to be ready to explore your ideas in great (and sometimes tiring) detail if you want to succeed. If any of this is feeling too hard already, question whether you’re truly committed to this idea.

Do you still want to solve this problem?

Good. Let’s move on.

In the third part of this series we delve into three different scenarios and come up with ways to help each one take the right next step.